By Andrew Haeg

Minnesota Public Radio

June 10, 2002

3M celebrates its first 100 years this week. Over the past century, 3M scientists have created a long and storied legacy of new and lucrative products, such as Post-It® Notes. Now management is transforming the company to make it grow more quickly. But some of the company's most prominent names say those changes may threaten 3M's unique, century-old culture of innovation.

| |

|

|

|

||

3M's annual meeting is always something of an extravaganza. Thousands of shareholders and former employees travel from around the United States to St. Paul, for a free lunch and chance to see the company up close.

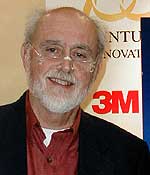

Attending this year's meeting last month was Art Fry, inventor of the Post-It® Note. Fry retired 10 years ago, but still works as a consultant with the company. Today he's worried that 3M is changing, and not for the better.

"There is a change in culture, and it is cause for concern," Fry says.

In the old days, Fry says 3M gave employees like himself a great deal of freedom to determine what ideas would make it to market. Now, he sees 3M management taking more control.

To Fry, the shift in culture is evidence of a troubling transition at the company.

"The main change is from an egalitarian type of culture - where anyone can assume leadership if they have an idea - to one where it's more of an elite culture, where only the people at the top control what gets done," he says.

Fry worries that changes could stifle the employee initiative that's been key to the company's success. He's not the only one who's concerned. Lewis Lehr was CEO of 3M from 1979 to 1986. He also wonders whether the company's new management programs will chill innovation.

"If you build a bureaucracy, you will ultimately stymie the program. That is one point that must be taken into serious consideration. Because bureaucracy can ruin anything," Lehr says.

Current 3M CEO James McNerney says innovation remains paramount, but he insists the company has to change. He says what was sufficient in the days of Lehr and Fry isn't now.

| |

|

|

|

||

"There is no question that we are going to be in a more competitive world in the next 20 years with our mix of products than we were in the last 20. I am one who believes that some additional structure and rigor in your choices about products, in investments in technologies, needs to be made," says McNerney.

There is a great deal at stake for the company and Minnesota if 3M's idea machine falters.

For the state, it's the future of a $16 billion company that employs 20,000 people in Minnesota, 70,000 worldwide, and is the only Minnesota company in the Dow Jones Industrial Average.

3M's founding families created major philanthropic organizations, like the Bush and McKnight Foundations.

What's at stake for the company is a proven formula for success, and a unique corporate culture, that traces back to the company's start 100 years ago.

3M began with a mistake.

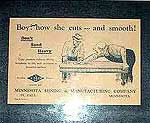

The five men who incorporated 3M on the North Shore of Lake Superior did so hoping to sell a great deal of a valuable mineral called corundum. Manufacturers back east used corundum for the grinding wheels they needed to finish their products.

The quintet thought the North Shore was abundant in corundum. They sold one load.

Then, on June 13, 1902, the five men walked into a small Two Harbors office of company secretary John Dwan, which is now part of the 3M Museum. They signed the papers making Minnesota Mining and Manufacturing a corporation.

|

"Mistakes will be made. But if a person is essentially right, the mistakes he or she makes is not as serious, in the long run, as the mistakes management will make if it's dictatorial and undertakes to tell those under its authority exactly how they must do their job. "

- William McKnight, first president of 3M |

But Dwan and his associates weren't selling what they thought they were selling.

"It was a well-kept secret that what they had found was not corundum." says Shelly Maloney of the Lake County Historical Society, which runs the 3M Museum in John Dwan's old office building. The mineral was anorthosite, and it was worthless.

The businessmen tried and failed to make sandpaper with the anorthosite. Rather than give up, they persevered, making sandpaper instead with imported minerals like Spanish garnet, and sandpaper sales grew strong.

The company's second big problem came in 1914.

Customers started complaining the garnet was falling off the paper when they started sanding. Soon a worker noticed that the minerals left an oily residue when soaked in water.

The garnet had travelled from Spain, along with olive oil, in the hold of a Spanish ship. Rough seas spilled the oil into the minerals, and the oil in turn kept the garnet from sticking to the cloth.

But 3M couldn't chuck the garnet - it was vital inventory. Instead, they had to find a way to get the oil out.

"What they found out is that if they first washed it and then baked it, then the oil would dissipate and they could use it," Maloney explains.

It took years for 3M to restore its reputation. But the company's early misadventures taught 3Mers an important lesson: ingenuity and perseverance can overcome even potentially ruinous mistakes.

In 1916, company general manager Willliam McKnight was determined to make sure that quality problems would never sink the company. That year, McKnight bought the company's first lab for $500. From then on, science would be 3M's guide.

| |

|

|

|

||

From then on, science would be the key to quality control and new products.

Sandpaper sales rebounded. Growth continued in the 1920s with sales of waterproof sandpaper. In the 1930s, 3M introduced Scotch® Tape.

Despite success, in a scratchy recording from the mid-1950s, McKnight admitted wondering how to keep the company growing.

"After having spent 50 years, and seen it grow from a very small, almost bankrupt company in 1905 to its size today, I often ask myself where this growth can be continued. And I am of the personal opinion that barring national emergency, the growth can be continued. And my reason for feeling this way is that first of all, we have great confidence in people," McKnight said.

Left to try and fail on their own, McKnight believed 3Mers would always dream up new, lucrative products.

"Mistakes will be made," McKnight wrote in 1948. "But if a person is essentially right, the mistakes he or she makes are not as serious, in the long run, as the mistakes management will make if it's dictatorial and undertakes to tell those under its authority exactly how they must do their job. "

"McKnight realized that everybody was smarter than he was in some area," Post-It® Note inventor Art Fry says.

Like other 3M scientists, Post-It® Note inventor Art Fry could spend up to 15 percent of his time on unauthorized projects that he found interesting. It was company policy.

In the 1970s Fry heard a 3M scientist talk about an adhesive that didn't stick well. Fry mulled it over and realized paper backed with a flawed adhesive could make a perfect bookmark. Fry and his colleagues persisted amid skepticism, and convinced their colleagues to use Post-Its. The idea finally made it to market.

| |

|

|

|

||

Fry credits McKnight for building a company that gave him the freedom to pursue the opportunity.

"McKnight reaized that individuals would see opportunities that he couldn't see. And if he allowed everybody to have time to work on opportunities that he saw, then they would see opportunities for growth that management could not possibly see," says Fry.

3M scientists developed masking tape, audio tape, Scotchgard®, reflective tape, and more recently, new screens for laptop computers that extend their batteries' life.

The creativity of 3M scientists would be less well known had the company not been equally innovative at selling. 3M's marketing and sales people were adept at taking basic technologies and finding new ways to package and sell them.

In a commercial from the 1960s, for instance, a singer extols the virtues of using Scotch Hair Set Tape.

"Scotch Hair Set tape is new, it's made for setting hair. Scotch hair set tape is soft, gentle to skin."

3M's ability to grow through innovation has remained consistent over the past few years. But in the late 1990s, its stock price stagnated. In 2000, for the first time ever, 3M chose an outsider to run the company. James McNerney, a former top executive at General Electric, took the helm.

He pledged to boost growth by cutting back slower growing divisions. Between April 2001, and the end of this month, 3M will have cut 6,000 jobs company wide. Meanwhile, McNerney has shifted more resources to faster growing businesses, like pharmaceuticals.

One product 3M touts is Aldara, a cream that treats venereal warts, and potentially other skin diseases. Last year, Aldara accounted for more than $100 million in sales, making it one of those fast-growing divisions McNerney favors.

Corporate scientist Richard Miller championed the development of Aldara. Like some critics, Miller says 3M faces perils as it tries to become more rigorous and disciplined, but he supports many of the changes McNerney is taking.

"The people in those divisions that are not allowed to grow - or maybe not allowed to exist as they were in the past - some of those I'm sure see change as a bad thing. But I think overall for 3M it will be seen as a good thing," says Miller. "To be a viable, growing company in such a competitive environment that we have today, you really have to focus your resources."

Focus is a popular word around 3M these days. So are two other words: Six Sigma. Six Sigma is a management program designed to improve quality and reduce waste. It was made popular by McNerney's former employer, General Electric.

Skeptics say Six Sigma poses a threat to 3M.

|

"In a company that's really driven by creative thinkers - how do you do Six Sigma and creativity? You can't. And if you force that model on an organization, you're just bound to make it moribund."

- Ryan Mathews, business consultant and critic of Six Sigma management |

"The whole notion of Six Sigma is to remove the deviation; clinically and surgically remove any possibility of error in the name of quality," says business consultant Ryan Mathews, who co-wrote The Deviant's Advantage: How Fringe Ideas Create Mass Markets, which examines the innovative process at 3M and other companies. "So you get very, very, good at what you used to do, and generally always at the expense of what you might possibly be doing."

Mathews says 3M was built by scientists who took calculated risks, and sometimes failed. Impose a strict regimen on a culture that embraces risk, and Mathews says you could end up squelching inspiration.

"In a company that's really driven by creative thinkers, how do you do Six Sigma and creativity? You can't. And if you force that model on an organization, you're just bound to make it moribund," Mathews says.

McNerney has heard such concerns before. But he says he understands the importance of innovation as much as anyone.

"The DNA of this company supports idea generation. I don't want to kill that, I want to support that. I just want to make the assessment of our ideas to be more rigorous," McNerney says.

He says times have changed. In years past, he says 3M could afford to be a little less efficient than it has to be today.

"I don't think it had to be as rigorous. I don't think the world was as competitive. Some of our technologies are new and exciting, and some of them are mature. You've got to manage those rigorously," McNerney says.

Bill Coyne, retired 3M senior vice president for research and development, believes McNerney's found the right balance between discipline and innovation.

"It is very tough to manage an innovative climate, because you can't set a direction and say, 'That's the only way I'm going to go.' You have to respond to ideas and opportunities as they come out of our organization," says Coyne. "So it's more of a bottom-up building of a company rather than a top-down. As you need more top-down direction and discipline, that has to meet at the right spot to not affect the innovative spirit we have at 3M. But we have a very good balance at the company now and I think we will into the future."

3M's investors seem to agree with Coyne. Since McNerney's arrival, the company's stock price has defied the downdraft on Wall Street and reached all time highs.

And if history is any guide, 3M might turn today's challenges into opportunities.

More from MPRMore Information